It's no secret that as early as the 1920s (if not before), automobile dealers – especially those selling used vehicles – have been accused of employing questionable ethics, often escalating into outright chicanery. In their reasonable quest to sell as many cars as possible, at the highest possible price, each dealer and salesperson has faced the temptation of spicing up a strong sales presentation with a misleading claim or intimidating tactic.

Inevitably, while the majority of car sellers have remained within the confines of ethical behavior, perhaps with an occasional deviation to attain a much-needed sale, some strayed considerably further into the realm of less-honorable practices.

More than most retail businesses, used-car dealers have often been vilified by the public. Rather than a respected businessman or merchant, they've been perceived as relentless deceivers eager to separate the customer from his dollars by any means necessary.

"Hard sell" practices were well developed by the 1930s, stimulated at least in part by actions taken by the nation's automakers. Those manufacturers, for instance, had begun imposing quotas on the number of new cars that had to be sold by each franchised dealership. Indirectly, at least, such quotas also affected the sales of secondhand vehicles. When the industry faced what appeared to be a saturation point, too, with sales of both new and used models sagging, something had to be done to clear out the stock of unsold vehicles that was accumulating at each dealership. The need for additional sales, despite having fewer likely prospects at hand, clearly called for more intense, aggressive efforts to get signatures on sales contracts.

Suspicious customers, then, were likely to accuse the dealer of malfeasance if anything in the transaction seems questionable. They'd probably heard or read horror stories about purchasers being "taken" (that is, cheated) in some way, winding up paying more than expected or with an automobile that turns out to fall short of any promises made to consummate the sale. As such car-shopping tales were publicized, whether in print or by word of mouth, they tended to tarnish the entire cohort of automobile dealers, affecting and branding the dutifully honest along with the malefactor.

By 1937, dealers were complaining of "unfair trade practices." The National Automobile Dealers Association (NADA) asked the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to set up a conference to investigate problems in the auto trade. Because of World War II, that FTC study was never completed.

Unethical and questionable tactics have included:

• Misrepresentation, ranging from exaggeration to light falsehoods, all the way to outright lies.

• Mechanical fakery, even including such extreme measures as pouring sawdust into gearboxes to quiet the gears (an allegation that dates back to the early days of motoring). How often such flagrant actions actually were taken is open to question.

• Overly-robust detailing (cover-up of body flaws).

• Speedometer rollbacks.

• Price trickery, including the bait-and-switch, lowball, balloon notes, and more. (See detailed explanation of these tactics later in this chapter.)

• Kickbacks to finance companies. The impact of lenders was stronger than ever, as some dealers obtained more profit from the financing than from the car itself.

Naturally, some tactics employed to ready a used vehicle for sale were wholly ethical – indeed, desirable. Normal reconditioning, for instance, was growing steadily under specific brand names: Chevrolet "OK," Buick "Gold Seal," etc. Warranties were developing (though some were deemed phony, or unclear about which problems were covered).

Flamboyant and questionable sales tactics reached their pinnacle in the 1950s, with the development of what came to be called "the blitz." No, we're not talking about a military invasion during the Second World War. The "blitz" of the 1950s was created by automobile dealers, seeking boldly effective, if less than wholly ethical, methods to sell as many cars as possible. By 1953, what one observer described as "fierce selling" to a "buyer's market" was taking place, with new cars selling at well below list prices. In concert, dealers were offering over-allowances on their used cars. At the height of the blitz, used-car prices dropped sharply.

Various dubious sales methods developed during the 1930s or the early postwar years were reaching new peaks of finesse. Perhaps best known was the "pack," whereby a new-car dealer offered uncommonly high allowances for trade-ins, while jacking up the new-car price by a similar amount. Highballing, padding, and other insidious techniques employed by unscrupulous operators made life difficult for totally honest dealers. Some of the tricks were reminiscent of the antics of old-time confidence men, such as "Yellow Kid" Weil, who had been using "big con" methods to bilk unwary but well-to-do men as early as the 1890s.

New-car dealers faced trouble with the government over sales practices, leading to hearings in the mid-1950s. In May 1955, striving to boost its image, the National Used Car Dealers Association was renamed the National Independent Automobile Dealers Association (the name it retains today). Flagrant "blitz" tactics would end after a few years, but some dubious used-car sales procedures hung on for a while longer. Or in some cases, a lot longer.

If deceitful behavior was worse than before the war, was it entirely the fault of the dealer? Had he become more nefarious? Or was the increase in dubious practices due in part to actions by automakers (including sales quotas and overproduction), to hard-to-please car buyers, to questionable procedures from finance companies. Or, did it stem from a decline in the general pattern of business ethics? At least some analysts might answer "all of the above."

Sometimes, an image in one field can carry over into other territory. Democrats ran campaign ads against Richard Nixon (a Republican) in his run for the presidency, asking "Would you buy a used car from this man?" Just about everyone seemed to understand that this query implied a possible lack of honesty.

How used car sales differed from other retail endeavors

In two distinct but directly related ways, marketing and selling of used cars has always differed substantially from retailing of other products:

1. Prices are flexible, not the least bit absolute.

2. No two used cars are alike.

3. Bargaining is acceptable, even if not quite encouraged.

Bargaining is nothing new, doubtless reaching back to pre-history. Probably, it developed during the first commercial transactions among primitive folk, when one slick caveperson sought to benefit himself while trading goods with a stranger (or with his compatriots). His motivation, like that of his modern-day descendants, was simple: an innate desire to give as little as possible, while gaining as much as possible.

No reason that elementary desire wouldn't remain, hundreds of millennia later. Prior to World War II, some analysts promoted the development of agencies that could establish fixed prices for secondhand automobiles. Such "clearing houses" setting prices wouldn't work, insisted auto dealer Martin Bury in his 1958 book The Automobile Dealer, because people like to bargain.

On the other hand, the common presumption that "everybody" bargains, invariably trying for the lowest possible price, is false. For some shoppers, the notion of dickering with an auto salesperson is practically tantamount to torture. At least a few of us really do prefer to shop on a take-it-or-leave-it basis, either accepting the seller's price or saying no and walking away, hoping for a more appealing "deal" elsewhere.

Still, every automobile dealer frequently faced the old "horse-trader" mentality: a presumed preference for bargaining on the part of customers, established as veritable gospel in the 19th century, long before automobiles arrived.

In the retail automotive world, there's generally been a substantial disparity between asking (list) price and the actual selling price of a car, whether new or used. That's where profit is derived, after all. What's called the Manufacturer Suggested Retail Price (MSRP) for new cars can be valuable as a means of comparison, but numerically at least is semi-fictional. For used cars, of course, the original MSRP is of little interest except as an indicator of the vehicle's original position in the spectrum of pricing.

As a rule of thumb, dealers tended to expect more profit from the sale of used cars than new ones, helped by less overhead. "Washout," incidentally, is the amount of profit attained after all the used cars in a sequence have been sold (that is, the final trade-in has gone to a customer). It could differ considerably from actual, individual profit figures derived from each transaction.

Late in the 1950s, the Chicago Tribune conducted its "landmark" study of the used-car market. For the first time, a study revealed who buys used cars, what they want, how they buy, where they buy, what they pay, and much more of interest to marketers

Pierre Martineau, research & marketing director for the newspaper, warned that used-car dealers needed a better image. Based upon his "depth" studies of consumer behavior, he advised the auto industry to make appeals to customers' emotions, not emphasizing price alone. Those sales appeals should focus on such factors as approval by others, sex, pleasure, ambition – even fear and envy. The psychological studies analyzed the shopper's inner motivation to purchase, ignoring the usual surface factors.

Martineau's study found that used-car buyers were 5 to 10 years younger than new-car buyers, and that 70 percent of them would like to own a new car. Prestige and appearance were most important to low-income buyers, while higher-income customers were more concerned about mechanical reliability. In that pre-digital age, buyers typically scrutinized classified ads in the local newspaper to determine typical prices for vehicles that interested them.

Two out of three participants in the study readily paid the asking price (no bargaining). Haggling over price was typically associated with "lot operators." Evidently, that designation referred to the tackiest, open-air used-car lots with vehicles packed tight and overblown claims promoted on flashy display signs.

One-third of those studied bought a vehicle from the first dealer visited. More than half (55 percent) bought from a franchised dealer, 15 percent from a used-car lot, and a whopping 30 percent from a private seller. Today, of course, in the 21st century, private sellers constitute a considerably smaller source of secondhand vehicles.

Martineau said that guarantee stickers and other such inducements imparted confidence. In 1957, some 4,000 dealers were giving buyers a 1-year used-car guarantee from a particular bonding company. The guarantee applied only to cars 5 years old and younger, which passed the bonding company's evaluation. Some dealers were said to have offered not just 1-year, but 2-year, or even "lifetime" guarantees.

Some shoppers, Martineau advised, bought used cars because of low self-esteem (feeling weak or inadequate). In effect, according to this theory, they wound up buying an automobile that was like themselves.

Shoppers with less-than-full wallets might also have noted that a better used car could actually convey more prestige than a cheaper-brand-new model. Unlike products in almost all other businesses, too, a used car is by definition always one-of-a-kind. Dealers in the Fifties, following the basic rules of economics, naturally catered to modern preferences for deluxe cars, preferably with plenty of options, over common makes and models with few extras.

Motivating the Customer

One contemporary observer noted several distinct customer types: the bargain hunter; the statistician (who claimed to know all the car prices); the amateur (or pro) mechanic; and the dreamer (the unfortunate soul who had vivid fantasies but few bucks). Another possibility was the overburdened fellow who owed more on his trade-in than it was worth. (In the 21st century, such a customer would be declared "underwater.") Salespeople might also expect to encounter an occasional wife who didn't want her husband to buy a car, as well as a few shoppers who fit into none of these categories.

Dealers were using more merchandising aids to move used cars as the Sixties approached, but some observers wondered if those promoters really didn't know how to sell in the traditional manner. By 1961, such giveaways to customers as mink coats might have been gone, for the most part; but lower-cost bonus gifts were still used. Auto factories even promoted sales contests for their dealers, which might have been asking for trouble. Sales contests present certain opportunities for deception, and not all dealers could resist. Like sales quotas, contests could lead to over-allowances for trade-ins and high used-car stocks by both new- and used-car dealers. There was almost invariably a trickle-down effect to independent used-car dealers, too.

Not every aggressive tactic employed to move the merchandise was illegal or unethical, of course. Most were viewed simply as effective salesmanship or imaginative marketing. Plenty of wholly legitimate dealers advertised loss leaders, pushed temptingly low dollars-per-month appeals, and promoted seemingly impossible selling prices. Some of the latter really were impossible, however, sending the offending dealership into a category closer to duplicitous.

Unlike new-car dealers, which focused on the makes they sold brand-new, the independent used-car dealer handled many makes. Each had specific merits to be highlighted. Fords and Chevrolets promised low maintenance costs and high resale value. Buicks were promoted for their soft ride; Nash and Studebaker for their fuel economy. Different sales appeals were typically employed for the three used-car categories: low-priced, popular-priced, and quality. Prestige was the top selling point for Cadillacs, Lincolns, and Packards.

In addition to the recommendations in the Martineau study, used-car dealers were advised in the 1950s to use emotional appeals, not just price. That meant emphasizing such factors as approval by others, efficiency, prestige, safety, pleasure, ambition, sex (of course), competition (envy), imitation, fear, hunger, and modesty. Quite a selection.

Auctions Move In

Most cars on a typical used-car lot, especially in later years, were not trade-ins. They'd been purchased at a wholesale auction, based upon the likelihood that a vehicle could be bid on and purchased, and then resold at an adequate profit.

Already in 1959, more than 150 wholesale auctions were selling some 20,000 cars per week to dealers. Auction popularity was largely a postwar phenomenon. Before World War II, dealers transacted mainly with wholesalers, which in turn connected with the vehicle manufacturers.

When evaluating an ordinary trade-in, the dealer should at least have attained a fair idea what he was buying. When the used car went through an auction, not so much. Today, more careful, intensive inspections make assessment prior to sale far more accurate.

To those not in the auto trade, a modern-day auction takes place so rapidly that it seems like the prospective buyer cannot possibly make a valid judgment of a specific automobile in the passing parade. But experienced evaluators can, and do, one after the other. In recent times, too, actual auction prices (published in scheduled reports) rather than individual trade-ins are used to establish market values.

Reconditioning, Then and Later

Preparation of cars for front-line display was changing during the Fifties. Engines and mechanical components lasted longer now. Dealers quickly realized that it was far cheaper and easier to do appearance reconditioning than to fiddle with major mechanical work. Before the war, reconditioning could have included such tasks as replacing piston rings or grinding valves, in addition to electrical and cooling-system work.

Now, reconditioning was more likely to involve touching up a fender scratch, smoothing a dent, replacing damaged glass, repairing a door lock, adding seat covers (perhaps to hide worn, poor upholstery underneath), replacing a floor mat, and cleaning upholstery. Under the hood, work would likely be limited to (at most) adjusting valve tappets, gapping or replacing spark plugs, or finessing a carburetor. And possibly, steam-cleaning the engine.

By the mid-1950s, new epoxy/fiberglass repair kits that permitted quickie "repairs" of rustouts and dents changed the concept of body reconditioning. Upholstery cleaners could make a stale interior emit a "new car smell." Plastic dyes could make interiors look like new (at least to the unwary). Body polish might give the exterior a fresh look, too.

Colorful Characters Threaten Dealer Image

Even before the outbreak of World War II, the car business was taking a new, flashier turn, relying on showmanship. In 1941, Earl "Madman" Muntz opened a used-car lot that would demonstrate the value of flamboyance in promoting sales. He established a certain tone for selling practices in his business, which a number of other dealers would soon adopt. His main competitor was said to be "Wild Tony Holzer," later known as "Honest John."

During his peak year, the "Madman" sold $72 million worth of used cars, and his lot became a popular tourist attraction. Muntz later became s Kaiser-Frazer distributor, and gave his name to a new, short-lived sports car.

California dealer J. Bob Yeakel was an early user of TV, remembered largely for advertising nonexistent (or not-to-be-sold) cheap specials. His misleading methods caused California law to be changed, requiring that license numbers be shown in ads.

H.J. Caruso was a particularly flagrant example of excess and deceit. A southern California new/used car dealer for 10 years, Caruso was found guilty of grand theft and forgery after selling some 40,000 cars. Caruso's illicit tricks included use of blank contracts, switching of documents, selling a customer's car (or replacing parts on it) while he was waiting, etc. He even operated a school for salesmen.

Many dealers took their role seriously, wishing to be considered regular businessmen. Law-abiding dealers who valued ethical business practices had a hard time overcoming the horrid public image created by the most egregious examples of lapsed ethics, many of which garnered considerable publicity and, as a result, public scorn.

Ralph Williams, who joined the California car business in the early 1960s, was among those of a different breed, stressing non-shady dealings. By 1968, he ranked as the biggest dealer in California, if not the entire nation. His chain of new-car dealerships sold some 2.3 million new and used cars in 1967 alone.

Serious-minded dealers could become local celebrities, too, or even expand their influence beyond the home city – especially if they made abundant use of TV. Chicago's Jim Moran, for example, was one of that city's first adopters of TV, appearing in his own commercials as a Hudson (later Ford) dealer, at Courtesy Motors. Because of those personal-style commercials, Moran was well-known in Chicago even by people who had little or no interest in buying a car. He was also among the first "supermarket" dealers, giving buyers a "lifetime" guarantee, though offering no actual servicing at his location.

Ever since the 1920s, many larger cities had a specific "automobile row," a stretch of street that held a string of automobile dealerships. New York had a wholesale row in the Bronx. Chicago's Western Avenue was the place to go for a variety of dealers and makes. In Detroit, Livernois Avenue, all the way from Eight Mile Road to Grand River, was the location of a large array of dealerships.

During the Muntz era, New York had its "Smiling Irishman;" Chicago had the "Angel of Broadway," operating four lots. Rusty Eck (known as the Wichita "Fordman") might be considered a 1970s version of Muntz.

Sticking To "The System"

In 1955, what came to be known as "the system" for selling new automobiles, was at its peak. Those dealers who bought the concept got the step-by-step details of the "hard sell" down pat, and followed the outline closely. Even if not illegal or illicit, such antics hardly conveyed an image of integrity.

Heavily scripted, these carefully planned auto dealership scenarios were not unlike the "canned," formulaic spiels delivered by door-to-door encyclopedia salesmen in those days. Even if they applied mainly to new cars, used cars were affected at least indirectly by dubious sales techniques, even if they were wholly (or almost) legal.

Most of the pricing trickery was related to trade-ins. Here are some of the favorites from the Fifties:

• Bait and Switch. This is an old-timer, used to trick shoppers for a variety of products. An advertisement displays a photo of a well-equipped car, accompanied by the price of a stripped-down version, to entice customers. At the dealership, the avid customer is shown the stripper, but swiftly switched to the loaded example with its higher price.

• Lowball. The salesman quotes a price below current market value, to encourage you to return and see if that offer is still valid, before turning to another dealer. At that second visit, the salesman informs you that the sales manager won't sell the car for that low price.

• Highball. You're quoted a high trade-in allowance for your old bus, but aren't quite ready to buy. Then, when you return later for a second look and possible purchase, the sales manager says "no" to that trade-in figure.

• Packing. Applying a "pack" meant that the new-car dealer offered an uncommonly high allowance for the customer's trade-in, while jacking up the new-car price by a similar amount.

• Padding. While filling out the sales contract, the salesman or other dealership employee pushes a few additional items, each of which adds a profitable extra charge to the total price. Such extras might include undercoating, paint protection, dealer-installed options, and/or credit life insurance. In more recent times, extended warranties have been prominent as last-minute add-ons.

• Balloon Note. This financing-based bit of misrepresentation has been used for decades as an adjunct to selling a variety of products. To entice the buyer, an unusually low monthly payment is specified. Trouble is, at the end of the loan term, that buyer learns to his dismay that the final payment will be vastly higher than he's been paying all along.

• Takeaway. If the customer is interested in a particular vehicle but not ready to buy just yet, the salesman might suggest leaving your trade-in at the dealership and taking the new (or new-used) car home overnight. No other dealer gets to see or evaluate your trade-in, while you're showing friends and neighbors your prospective purchase. By the next day, when you return the car, you might have a hard time saying "no" to the purchase. The term "put to ride" has been used to describe this scenario.

• Good Cop/Bad Cop. Much like the interrogation method favored by police detectives (at least on TV), at the dealership, the salesman fills the role of the "good guy:" The sales manager is the baddie. The duo's goal: to enhance the image of the salesman so you're more likely to favor him. They might even stage a fictitious argument, with the salesman struggling to convince the manager to give you, the customer, a better price. If you believe the salesman is indeed your friend, you're more likely to buy.

• Personalization. Salesperson keeps referring to the on-sale vehicle as "your car," or otherwise makes it sound like the deal is already completed. Subconsciously, you're made to feel almost as if you already own the car; thus, easier to get you to sign the contract, having a "personal stake" in the car.

Speedometer rollbacks remained a problem, too. One expert in 1960 estimated that 80 to 90 percent of used-car speedometers had been turned back to a lower mileage figure. That practice was illegal in only two states. Not until 1986 would the federal government step in with the Truth in Mileage Act, which required disclosure of a car's mileage at the time of sale.

"Bootlegging," which had been a concern back in the 1920s when market saturation appeared to be serious, persisted for a while into the Fifties. Some analysts thought a similar saturation threat might be looming by decade's end. Because of overproduction, they once again wondered if everyone who wanted a car already had one.

As before, bootlegging meant that franchised dealers would sell some new cars to independent used-car dealers, who then sold them at lower prices than the legitimate dealers. A number of dealers accepted sharply lowered markups on new cars: just a few percent, far below the prior 25 percent or so that had been typical.

Whether they were 1950s refinements of earlier new-car tricks or brand-new examples of duplicity, their descriptions are hardly the kind of terminology that suggests ethical practices. Only about 40 percent of dealers were estimated to use these tactics, mainly in big cities. Yet, they tarnished the whole "profession" of automobile sales. Virtually all dealers were presumed to be dishonest by the general public. By the mid-1960s, most of the ethics-challenged sales methods had become illegal, but they never quite disappeared.

Private sellers, it must be noted, are not without their own bag of tricks. In the Sixties, to take a personal example, a friend of this author bought and sold a number of cars over a several-year period, without the benefit of a dealer's license or a business location. That amateur dealer might never have heard the term "curbstoner," but that's how the transactions operated, often including making false or misleading claims about a car's history, accident record, and the owner's driving habits. A car described as "one-owner, garage-kept, low-mileage" may or may not have qualified for any of those adjectives. Suggestions that such antics amounted to taking advantage of one's neighbors and strangers alike, whether flagrantly or slightly (perhaps by omission), were ignored.

The Critics Speak (or write) ...

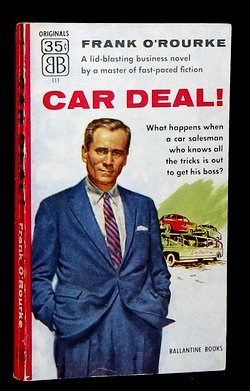

Frank O'Rourke wrote a novel. Car Deal!, published in 1955 as a 35-cent pocket book, intended to protect buyers and help get rid of crooked sellers. Despite its being fiction, he described most of the popular tricks and practices.

Many other books and articles have been written, especially in later years, claiming that their instructions would let the reader overcome the hard-sell tactics at the local dealership, and avoid the most diabolical operators. No telling how many buyers read them or abided by their recommendations.

Several well-known authors penned books describing insidious techniques employed by shady car dealers and their employees, as well as questionable practices devised by the automakers. Some of them were formerly in the business; others were journalists, social critics, or even humorists.

John Keats published The Insolent Chariots in 1957, creating an amusing and lighthearted, easy-to-read yet seriously concerned, appraisal of the entire American auto industry. Vance Packard issued The Hidden Persuaders in 1957 as well, focusing mainly on manipulations devised by marketers for the manufacturers, whether they produced and sold cars or other commodities. Notable insights on the role of the automobile in American life could be gleaned from another of Packard's nonfiction books, The Status Seekers (1959); and even from the works of sociologist/economist Thorstein Veblen, who had coined the term "conspicuous consumption" way back in 1899.

Said one relatively modern author: ever since the 1930s, used cars have been "the province of flamboyant orators who used every trick to disguise the fact that they were selling something that some other consumer no longer wanted." Humorist Andy Rooney, a regular commentator on CBS' 60 Minutes, expressed it even more succinctly: "By the very nature of the business, those ... dealers are selling faulty merchandise."

It was perhaps no coincidence that one main character in the aptly-titled 1957 film No Down Payment was a car salesman, attempting to seduce a rustic couple who could barely afford a new wheelbarrow into signing up for a loaded, deluxe pleasure palace on wheels.

Complaints of unfair trade practices went back to 1937 and the Federal Trade Commission study that was never completed. Congress held hearings on the automobile trade in 1956, though they dealt primarily with new-car marketing practices. During the hearings, it was revealed that GMAC had two distinct finance-rate charts; the dealer seeking a bigger kickback used the higher-rate chart.

At the time of these Senate hearings, 10 percent of national income was spent on cars and there was one car for every three people. In 1958, the Automobile Information Disclosure Act mandated a price label for new automobiles, but nothing was done regarding used vehicles.

In 1952, a 15-minute "empathy test" was shown to be a good predictor of success for new-car salesmen, while it failed utterly with used-car salesmen. Over-the-top, truly fraudulent practices became less common over the next decade or two, but the image of that hearty, smiling salesman, possibly ready to employ some form of trickery or deceit, hung on a lot longer in the public mind.

Click here for Overview: Casual History of the Used Car

Click here for Chapter 1: Early Days - Rich Men's Playthings, Poor Men's Dreams

Click here for Chapter 2: Ford's Model T and the Masses

Click here for Chapter 3: Production and Prosperity

Click here for Chapter 4: "Easy" Payments

Click here for Chapter 5: Family Cars and Family Life

Click here for Chapter 6: Five-Dollar Flivvers

Click here for Chapter 7: Rise and Fall of the Used Car

Click here for Chapter 8: Saturation and Salesmanship

Click here for Chapter 9: A Global Blowout

Click here for Chapter 10: Selling in Hard Times

Click here for Chapter 11: Wheels for the Workingman

Click here for Chapter 12: Okies, Nomads, and Jalopies

Click here for Chapter 13: Motoring in Wartime

Click here for Chapter 14: The Postwar Boom

Click here for Chapter 15: Chromium Fantasies

Click here for Chapter 17: Wheels for the Fifties Workingman

Click here for Chapter 18: Teens, Rods, and Clunkers

Click here for Chapter 19: Everybody Drives

Click here for Chapter 20: Personal History of Clunker Ownership